Otyugra

joined

A small studio making a horror-roguelike (Dream-Prison Wanderer), as well as a platformer/action/adventure hybrid (Phantomatics), each filled with our signature polish and uniqueness.

Hello. As with before, these are the bold consequences of designing a large-scale game with grid movement. Our game, Phantomatics, take the concept of a grid-platformer as laid out by games like Frogger 2 for the Playstation 1 and runs with it. Here's Part one.

Strange Truth #3:

Grid game worlds are easier to design

The self-imposed limits of a rigid grid mean the player has different expectations for a living world within a game. Grids are abstractions of reality, and as such, small movements on a grid can hold so much more meaning. If you see a character wandering around outside their house, perhaps your mind fills in the gaps that the character is doing yard work or looking for something, because who's to say?

This brings to light that using a grid can easily be a way of cutting corners, and I'm willing to own up to doing just that. When you're not a studio with a big budget or pull, coming up with ways to make corner cuts smarter is vital. That being said, simplicity and abstraction have a unique value and unique voice. In that sense, less is more.

Strange Truth #4:

Grids connect the past with the future

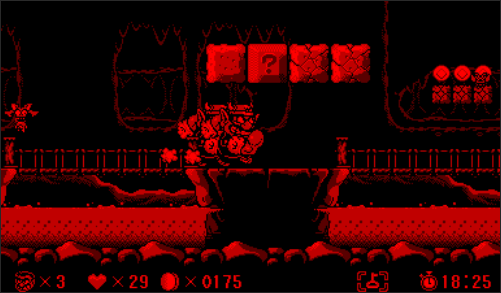

Wario Land for the Virtual Boy. A game that uses a grid despite the growing sophistication of the series.

As games have gotten bigger and better, hardware no longer relies on scanlines and rigidly placed rectangle sprites for their presentation, but all the same, grid design has always stuck around in subtle ways. Sure, maybe nowadays nothing conforms to those grids except the ground, but that alone can have a domino effect in which all free form objects must take into account the sublime simplicity of the world they're surrounded by.

The point I want to make is that its usefulness and natural choice for a foundation isn't going away anytime soon, which means grids are as much a part of old game design as it will be new designs. The difference will come elsewhere. Maybe making bigger worlds will become easier with technology, and games of specific sizes become doable with smaller and smaller teams as time passes. As you can see in the virtual boy game featured above, new technology comes into focus all the time, and for Wario Land, the player suddenly could travel not just left, right, up, down, but also back and forth between the foreground and background. Games are getting more sophisticated all the time, but grid thinking continues to be relevant even as games become more realistic or more impressive.

~ ~ ~

So there you have it. Using a grid prominently in a big modern game is an alternative way to experience adventure, and comes with development quirks. This says nothing about the unexplored possibilities of putting different genres on a grid (platformers like our Phantomatics are still an anomaly). Time will tell what grids will offer to gaming in the future, and I'm happy to be apart of that.

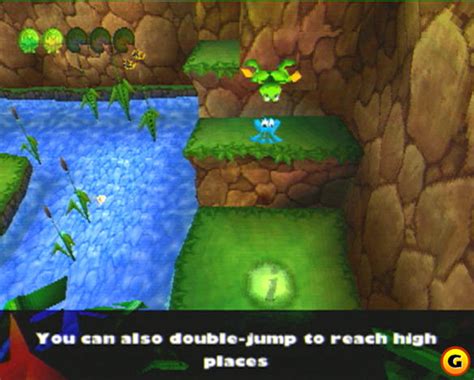

If you've ever played Frogger (1981), or an old Pokemon game, then you know you it means for a game to be on a square grid. Some grid games even made the jump to 3D! Frogger games for the PS1 had you platforming on a 3D grid:

About two years earlier, home computer games were experimenting with grid-movement in puzzle-platformers, such as Supaplex (1993), and Arcy 2 (1994):

So what if someone took the very unorthodox elements of grid worlds, and put them into a "modern" game? How would it look for modern game design and a lack of limitations to fully embrace the seemingly-backward nature of having everything put on big clunky squares? That's exactly what my team is eager to find out! So far, we've discovered some counterintuitive things about designing a huge grid game.

Strange Truth #1:

Making a grid game is like assembling a 1,000-piece puzzle

Even though we are making this game through GameMaker: Studio, we have built half on an engine on top of GameMaker to get around its limitations. For example, we wanted for ours to add and delete vertical columns that shift into or out of the viewing field. This means we needed to have a series of matrices that are put under a small projector-like sub-program that displays a small portion of each matrix at all times.

This is what the game looks like prior to moving the camera a "single unit" (three squares over):

This is the appearance after pressing the camera-move button at the bottom left:

This means that if something (like a tree) is larger than a single square block, it helps to split it up into squares so that it can be easily moved, added, and deleted by the square. So that begs the question, how many squares would need to be added individually because of this way of doing things, and how tedious would that be? Well, this area alone ("Hickel Highway") uses at least 29 unique tile blocks, about half of which get repeated throughout the level. For a location you stay in for only about 2-1/2 minutes, we are required to add 29 objects into the project, give each of them an image, an index, ties with the main mechanics, and a location on the script that knows to draw each object upon moving the camera. That's about 50 seconds of work per 32x32 block on screen!!

Strange Truth #2:

Grids (can) turn all challenges into mini Chess games

Long ago, I wanted to make a game inspired by Chess in which you go through a series of scenarios with the pieces already placed and you need to figure out the best course of action in only a tiny number of moves to achieve a goal. When designing this current game, it occurred to me that Phantomatics is basically that, only bigger in scope and more exciting than what would seem like a mobile phone game. Rather than splitting the challenges into a checklist, Phantomatics shows you what it's like to live and breathe in a grid world, where small challenges come and pass like the flow of water.

In our game, you play as a robot (and a ghost at the same time, but I digress). This robot can only jump two blocks high, and can only move left or right at a maximum speed. Using this knowledge, the player can get a feel for where they can land after a jump, or how fast they can travel to escape a threat. This effectively turns the obtuse, number problem into a visual, friendly, spatial problem.

- - -

Trying not to get seen by a moving pokemon trainer in Pokemon Yellow Special Pikachu Edition is much like trying to think one step ahead of your chess opponent! This segues nicely into Strange Truth #3... which you'll have to tune in next time for! Be on the lookout for Part 2 of this article, or, follow this project to be in the know about the bizarre process of making a "modern grid game." Again, the name of the game is Phantomatics, so if you like point-and-click games, puzzle-platformers, action games, horror games, Tactical RPGs, OR story-heavy games, stick around to discover why this game is a good fit for you.

Till our paths cross once more. Matthew.