Armor and weapons in the Hellenistic world were varied, unique, and effective, spreading all over the world, from Greece to Asia Minor, to Egypt, to Carthage, Spain, Rome, and deep into Central Asia. Until the Romans rose to power, Greek equipment was the standard kit of most armies in the Mediterranean. Bronze was the main material used for making armor and helmets, while iron was used to produce weapons. Spears were the main weapon of the Greeks and Macedonians, who together form the Hellenistic civilizations. This was due to their form of combat, based around a square of heavy infantry known as a phalanx. And the two Hellenistic civilizations had their own versions of the phalanx: the Greeks used a phalanx usually eight men deep armed with short spears and large shields, while the Macedonians equipped their soldiers with pikes measuring 15 feet or longer and smaller shields in formations of 16 men deep.

Regardless of differences both armies emphasized heavy armor and protection coupled with discipline and teamwork. While the soldiers in Greek armies may not have been equally equipped, they trained together to the best of their ability allowing them to fight as a powerful unit. Powerful as the Greek hoplites were, the Macedonian phalangists eclipsed them in training, discipline and equipment, going on to conquer a large empire under Alexander the Great. Greek armor was strong and heavy by comparison to most other nations during the5th and 4th centuries BC, but Macedonian armor of the 3rd century BC was significantly heavier. Later Macedonian style cuirasses were extremely heavy, some weighing close to 100 pounds apiece. One was even tested by firing a siege weapon at it from less than 100 feet, stopping the large crossbow bolt with little damage to the cuirass.

While extremely protective, the heavy armor of the Macedonians was to become part of their downfall as the Romans began to invade the Eastern Mediterranean in the 2nd century BC. While Roman legionnaires were heavily armored like their Macedonian counterparts, they balanced protection with movement and agility. Combined with their more flexible form of combat, the Romans crushed Macedonian phalanxes, whose heavily laden troops were no match for their Latin conquerors. Hellenistic military history ends with the rise of the Roman Empire, but not before soldiers like Leonidas, Xenophon, and Alexander the Great had firmly engraved the Hellenistic military legacy in stone.

Armor – Ancient Greek and Macedonian armor went through several stages of development, but throughout the Hellenistic period bronze remained the armor of choice for foot soldiers and cavalry alike. Hoplites and Macedonian phalangists were often equipped with the best cuirasses available. In contrast early Hellenistic cavalry rarely wore armor, while later Macedonian cavalry like the Companion Cavalry were heavily armored. Light troops such as peltasts and archers were usually unarmored except for helmets.

Bronze

Throughout the Hellenistic period this was the prized cuirass, but due to its cost it was limited to rich citizens in the Greek city-states. The Macedonians were a professional army with money to spend on its soldiers, who were handsomely equipped with bronze armor. Consisting of a back and breastplate joined together at the shoulders and along the sides, the bronze cuirass provided protection against most forms of attack, even arrows as shown at the Battle of Issus. During the 5th century the bronze was used by a minority of hoplites, most using cheaper linen cuirasses, but in the 4th century BC bronze came back into style, evolving to some truly ludicrous specifications. Armor had been getting progressively heavier during the Macedonian period and eventually cuirasses began to weigh in the 100-pound range (not to mention the rest of the soldier’s equipment), turning the soldier a walking tank. Bronze cuirasses were often fringed on the bottom edge with rows of stiff leather flaps called pteruges to protect the groin and upper thigh. A popular option of bronze armor was to shape it like a male torso, displaying accented muscles. The muscled cuirass was popular not only with Hellenistic soldiers but with Romans officers, who wore them well into the 2nd century AD.

Linothorax

The usual image of hoplites is of them sporting this cuirass made of linen or canvas glued together in thick layers to form a tough but flexible (not to mention comfortable) piece of armor. Called a linothorax, the armor was popular due to the fact it was cheaper than a bronze cuirass and that it gave excellent protection. While strong, it was still not as durable as bronze, so it was often reinforced with scales made of the same metal. When taken off the whole linothorax could be laid out flat on the ground, being open on the left side. To put it on, the hoplite simply wrapped it around his body, tied it on the left side, and tied the shoulder straps that connected to the back of the cuirass to the front. When combined with a hoplon, greaves, and a suitable helmet the Hellenistic soldier was well protected and the most formidable warrior of his age. By the time of the Persian Wars in the 5th century BC the linothorax was extremely common in the ranks, the very rich being the only ones able to purchase bronze armor. The Macedonians also used the linothorax in their army to some degree as well. As with practically every piece of Greek military equipment, the linen cuirass spread all over the known world to be used troops in Italy, Carthage, Asia Minor, and Persia.

Iphikratean

In the 4th century BC an Athenian general by the name of Iphikrates noticed the power of peltasts and how they could devastate the slow moving hoplites. Therefore he changed the hoplite’s traditional panoply to make them lighter, faster, and more agile in order to dodge the peltasts’ missiles, while still remaining capable of fighting other hoplites. One of the main changes was the introduction of a quilted linen cuirass. While light and not as strong, it was able to absorb the blows of opponents, and if the weapon did pierce through, the linen would wrap around it and get in between the weapon and the flesh. This prevented more serious wounds and allowed for easy removal of javelins and arrows (simply pull on the linen around the entrance wound and the weapon pops out with less damage to body than if it was just yanked it out). Alexander the Great used anIphikratean cuirass, and was quite pleased with it, as were many Greeks it seems, for it become fairly popular. But at no time did it ever become a threat to the traditional bronze and linothorax armor.

Greaves

Greaves were standard equipment for hoplites rich enough to afford them, while poorer troops obtained them when possible. Made of bronze (and possibly iron), there were two types: one wrapped around the wearer’s legs being held in place by the pressure of greaves squeezing the leg, the other being tied onto the legs with straps. In some cases when a Hellenistic soldier could not afford two greaves, he would purchase one and place it on his left leg, the one he would hold forward in formation.

Helmets – Greek helmets were varied and unique, many painted and others adorned with elaborate crests. Front facing crests were the most common, but the Spartans were known to use transverse crest, possibly a sign of rank. All Hellenistic helmets were capable of accepting a crest, which was usually made of horsehair. One style of helmet that is not shown here is the Petasus, which resembled a broad brimmed civilian hat, which proved to be very popular with light infantry, missile troops, and early Greek cavalry. Hellenistic helmets evolved over time from the ultra-protective Corinthian to helmets that featured better visibility, hearing, and comfort, like the Thracian. As Hellenistic equipment in general became heavier in the 3rd century BC, helmets went with the flow, becoming thicker and stronger.

Corinthian

Probably the most famous helmet of all time, the Corinthian style was the preeminent helmet in Greece during the period from around 700 BC to sometime in the early 4th century. Crafted out of a single piece of bronze, the Corinthian provided excellent protection but restricted vision and made the wearer essentially deaf. This proved to be a major disadvantage in battle, since orders could not be given once combat had begun. Another problem was the fact that the helmet was very uncomfortable to wear, prompting hoplites to push the Corinthian up on their foreheads when it was safe to do so. The weight of the helmet may have been one reason why the Spartans grew their hair long, to provide a cushion for the heavy helmet. As time went on, the Corinthian was modified slightly by adding openings for the ears to overcome the hearing problem associated with the helmet, spawning a sub-style know as the Italo-Corinthian. Elaborate horsehair crests were worn by many hoplites, but were not universal with this wildly popular helmet. In the 4th century BC helmets trends turned away from the Corinthian and it disappeared from history.

Chalcidian

Related to the Corinthian, the Chalcidian helmet was an old style within itself (originating in the 6th century BC), and was used by a minority of hoplites during the reign of its more famous rival. Essentially it was a Corinthian with smaller, rounded cheek guards and holes for the ears, but some versions had square cheekguards. Providing slightly better vision and superior hearing, the Chalcidian helmet grew in popularity as the Corinthian declined. It was popular in Italy as well, where it was modified to use the characteristic large Italian hinged cheek guards. By the time of Alexander the Great, the Chalcidian was still worn by a quite a fewhoplites, but was definitely the back-up choice when compared to a Thracian or Phrygian helmet. As with the Corinthian, the Chalcidian could be adorned with a broad horsehair crest.

Illyrian

Probably the most ancient helmet design still used in Greece at the time of the Persian Wars was the Illyrian. The origins of this helmet trace back the ancient Mycenians sometime in the late 2nd millennia BC, making it the “grand-daddy” of all Greek helmets. While its ancestry is venerable, the actual Illyrian style did not appear until 7th century BC. The Corinthian is related to the Illyrian, differing slightly in method of construction and configuration. Instead of using a single piece of bronze, early Illyrian helmets were manufactured by pounding two pieces of bronze into the desired shape and then welded together on the crown, the seam often being covered by a crest holder. Later a single sheet of bronze was used, resulting in a heavy helmet that gave excellent protection to the head and cheeks. Configuration-wise the Illyrian was extremely similar to the Corinthian except that it had an open face with no nasal bar and smaller cheek guards. As with the Corinthian, the Illyrian style helmet rendered the wearer deaf and (as with the former) the Illyrian was also modified to allow for the ears to protrude outside the helmet. The Illyrian had become rare in the ranks by the time ofAlexander the Great.

Thracian

As the Corinthian style began to fade from the ranks of Hellenistic soldiers, the Thracian rose to become one of the most popular helmets for soldiers in the armies of Greece in the 4th century and of Macedonia. Appearing in the 5th century BC, the Thracian helmet was a bold change from the standard Corinthian helmet, featuring an open face and good hearing but not sacrificing protection. Long cheek guards protected the throat and face while the large bowl gave good coverage from sword strikes. The inspiration for the design of the helmet comes from the Thracian bonnet, worn by the inhabitants of Thrace, north of Greece. The name Thracian refers to the inspiration of the design rather than the actual place of origin, which was purely Greek. Over time the top of the helmet began to “flop” over on itself, like the Phrygian helmet. As with other Greek helmets, horsehair crests were worn but Italian style limp plumes were also used. Thracian helmets spread all around the eastern Mediterranean and into central Asia via Alexander the Great’s troops and the armies of the Successor Kingdoms. As with many pieces of later Greek equipment, the Thracian disappeared with the rise of the Roman Empire.

Phrygian

The Phrygian style helmet was characterized by a large flopping peak made to resemble a civilian hat and has been described as a “Smurf hat in bronze”. Typically this style of helmet did not have cheek guards, but was often equipped with a facemask worked to look like the bearded face of a man. Eventually the Phrygian superceded the Thracian helmet and became the preferred choice of Macedonian infantry. As with the Thracian, it disappeared when the Romans conquered Greece, Macedonia, Asia Minor, and Egypt.

Boeotian

As far as we can tell the Boeotian helmet was worn mostly by cavalry, the most famous users being the Companion Cavalry of Alexander the Great. In addition light troops such as peltasts and slingers used it. The main feature that endeared it to horsemen and missile troops was the excellent visibility, in addition to providing good defense against blows.

Pylos

Appearing in the 5th century BC in Sparta, the Pylos eventually spread all over Greece and Macedonia, equipping a large number of Alexander the Great’s troops. In addition it was popular among light troops such aspeltasts and archers, thanks to its low cost. Armorers of the ancient Hellenistic states based many helmets on civilian hats, a common ancestry of the Pylos, Thracian, and Phrygian style helmets. The Pylos was especially popular in the 4th century BC.

Attic

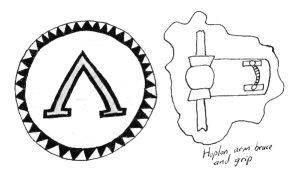

Descendent from the Chalcidian style helmet, the Attic was one of the new breeds of helmets that came into fashion after the Corinthian fell out of favor. Essentially it was a Chalcidian helmet with no nasal bar, the only remnants of the original feature being the inverted-v on the forehead of the Attic. It was popular in the Hellenistic world, being used by famous soldiers like Alexander the Great and Pyrrhus, often ornately decorated. In addition, the Attic was often equipped with hinged cheek guards, especially in Italy where it was widely used by the Romans and Etruscans, but the greatest admirers of the style were the Samnites, who used almost nothing else. The Attic lived on longer than any other Greek helmet, lasting until the 1st century AD in the Roman army as an officer’s helmet.

Weapons – Hellenistic heavy infantry used the spear as their main weapon in battle, backed up by a sword. In the cavalry javelins, spears, and swords were the main weapons, while light missile troops fought with javelins, slings, and bows, sometimes carrying a sword and (especially with later peltasts) the odd spear.

Xiphos

When a hoplite attacked his opponent the spear was his primary weapon, the sword being used mainly as a back up. The roughly 30-inch straight sword or xiphos was worn on the left side of a soldier and could be used for either slashing or thrusting. The xiphos was not limited to just the infantry, but was used by cavalry as well. More popular than the curved kopis, the xiphos was used throughout the Hellenistic period by Greeks and Macedonians. As with most pieces of Greek military equipment it spread rapidly through the Mediterranean, being adopted by soldiers from Rome, Carthage, Persia, and Egypt. It was used up until the early Roman Empire, when the known world was conquered.

Kopis

While the standard xiphos was a deadly enough weapon, the kopis had a renowned reputation for shear destructiveness. Its wide, heavy blade allowed for cuts that could crush through a helmet or slice off an arm with ease. Using a triangular curved blade, the roughly 25 inch kopis was a common weapon, easily substituted for the straight sword. The kopis was also used by the cavalry and when in the hands of an experienced swordsman the blade could cause horrific damage. Appearing some time in the 6th century BC, the kopis was used in one form or another for quite some time after that, spawning many different swords and bladed weapons. One was the falcata, which was used to great effect by Iberian warriors, the other being the Gurhkakukri fighting-knife, which is still used today by these elite British troops.

Thrusting Spear

Hoplites were famous for their use of the spear, which they preferred to all other weapons. When the phalanxadvanced towards their opponents, they would lock their shields together to form a wall facing their opponents. The hoplite would use his spear by holding it over arm, with the shaft over his shoulder and above the edge of the shields, and jab it forward into his opponents’ faces and throats. On average the hoplite thrusting spear was 8 feet long with an iron spearhead, and in some cases a counter-balancing butt-spike, which could be used offensively if the spearhead had been broken off. A common practice was to tie a leather grip around the middle of the spear shaft (commonly made of ash) to improve grip.

Sarissa

Each army has its signature weapon: the Romans had the gladius, the Huns the recurved bow, and the Macedonians had the sarissa, a pike that could reach lengths of up to 19 feet. Typically the sarissa was measured according to the position of the individual soldier in the phalanx, the farther back he was the longer his sarissa became. A soldier in the front rank would usually be equipped with a 15-foot pike, whereas aphalangist four ranks back might be wielding one of 19 feet. This allowed for the spears of the first few ranks to overlap, creating a labyrinth of pikes for their opponents to wade through. The spearhead was iron, which could be easily driven through the light shields and armor of the Macedonian’s Persian adversaries. The sarissawas so long that two hands were necessary to use it, the shield hung on the left arm and supported by a strap that wrapped around the soldier’s neck, which was attached to the shield rim. One instance where the sarissaproved valuable was at the Battle of Hydapses, where Alexander the Great’s army faced a large force of Indians supported by war elephants. The long sarissa was easily capable of taking out the mahout and the warriors perched on the backs of the elephants, not to mention stabbing the animal to goad it into stampeding back on its own lines. Later on the sarissa would be used by the Successor Kingdoms not only by infantry but soldiers in war towers atop the backs of their own elephants. Roman legionnaires encountered sarissa-wieldingphalanxes all over the eastern Mediterranean but by then the sarissa was no longer the supreme weapon of the battlefield, the tactics having changed, and as a result it faded from use.

Javelin

Peltasts were light missile troops used on the battlefield by Greeks and Macedonians, using a small 3 to 5 foot javelin. In battle peltasts would run towards their enemies and hurl their javelins into the ranks of tightly packed hoplites or, in the case of the Macedonians, Persian formations. Typically several javelins were carried by peltasts, probably around five, give or take a few depending on the size of the missile. The javelin would be equipped with a leather strap attached to the shaft, giving the peltast more leverage when throwing and hence greater range.

Sling

The Greeks were famous for their slingers, who were masters with this weapon, one of the most basic ever created. A rock or a lead missile was placed in the pouch and then rapidly swung over the shoulder at the target. An underarm technique was also used, but in either case the missile could be sent up to 360 yards, farther than a bow. The lead bullets were especially brutal when they hit, imbedding themselves deep inside the body of the opponent. They were capable of cracking a man’s skull wide open with one hit. Sometimes messages like “Take that” were engraved on lead bullets, many of which have survived to the present day. Rhodian slingers were championed as some of the best proponents of the weapon and were able to devastate opposing infantry, even enemy slingers. Slings were used by the Greeks during the Persian Wars and the Peloponnesian War, and by the Macedonians under Alexander the Great.

Bow

Archery was useful to the Hellenistic armies because of its usefulness in breaking up enemy formations, be they other phalanxes or Persians. The most famous archers in the world during the Hellenistic period were the Cretans, whose powerful Asiatic-horn bow was able to send arrows through the toughest armor. Another group of people that were prized by the Greeks and others as archers, were the Scythians, who often hired themselves out as mercenaries. Scythians made up the police forces of some ancient Greek cities, armed with an extremely dangerous recurved bow.

Shields – Shields were vital to Hellenistic combat, since protection and a shield wall were the basis of the phalanx. As a result, once the Greeks had developed the hoplon they used it for centuries, since it met all of their requirements. The pelta was used by lighter troops and was not seen in the phalanx.

Boeotian

The Boeotian shield was used earlier in Greek history, having been replaced by the 5th century and the Persian Wars. Structurally it had many things in common with the hoplon, its more famous rival, including a similar method of mounting the weapon on the arm, namely a brace in the center of the shield where the arm was inserted and a handgrip near the rim. It was similar to Persian shields in the fact that it had holes on either side, forming a rough figure eight. By around 500 BC the Boeotian shield had disappeared.

Hoplon

The hoplon is as traditional as Hellenistic equipment gets, being the shield that dominated the ranks of many armies for centuries. Constructed by taking a large piece of wood, hollowing it out, and finally coating it with bronze on both sides, the hoplon was easily capable of stopping any weapon. Arrows and javelins were easily stopped, if not deflected, and it would take a man of enormous strength and a spear of incredible durability to puncture the hoplon. While this protection was avidly sought after, it came at a cost since the hoplon weighed roughly 20 pounds. As a result, hoplites traded protection for speed, but it was well worth it since the shield covered a man from knees to chin. The hoplon formed an essential part of the battle strategy of the ancient Hellenistic armies, since it was used to not only protect the user but also cover part of his left-hand comrade’s body. In addition, the man to the hoplite’s right would be covering the exposed right side of the hoplite’s body and so on down the line of the phalanx. Of course this meant the right flank of a phalanx was unprotected, resulting in the tactic of always turning on the right flank in hoplite-on-hoplite battles. Like Crossing the T in naval battles, attacking an enemy phalanx on the right side allowed for maximum damage. As Hellenistic armor evolved, the traditional hoplite was modified to suit more specialized needs, such as shrinking and being made of wood and leather for Iphikratean hoplites and becoming slightly smaller for Macedonian phalangists (but retaining the wood-bronze construction). Despite this, the traditional hoplon continued to be used into the 4th and 3rd centuries BC. The hoplon continued to be used until the Roman Empire established itself.

Pelta

Peltasts originally were Thracian mercenaries who hired themselves out to the Greeks. One of the unique pieces of equipment they brought with them was the pelta, a crescent shaped shield. Eventually the word peltacame to refer to any shield carried by any peltast, be they crescent shaped, oval, or round. Made of wood or whicker, the pelta was light and allowed the peltasts to dart in and out at their much heavier opponents. In addition it gave them an edge if they ever engaged in close combat with other light troops. The pelta was carried by either a handgrip in the center of the shield or by the hoplon method.

This comment is currently awaiting admin approval, join now to view.