So I had the unfortunate opportunity to learn about component-driven development during a job interview for a potential internship at a mobile games studio. Despite the fact that I was geniunely interested in learning more about it and that I hoped to teach myself prior to starting the job, I don't think they were too interested in a student who knew nothing about the topic. Let's just say I didn't get that internship.

It's been a couple years since that interview and I like to think I'm at least slightly more knowledgeable about certain design patterns. So when it came time to finally design the engine which I was going to use for my first marketable game, I immediately decided that I should focus on designing it as an entity-component system. The decision was pretty easy considering how well Unity pushes the design pattern via the Inspector. My main goal though, even more so then using components, was to design an engine which I could add and edit with little development overhead. I wanted to simplify the process of creating new objects to the point where it would take me virtually no time to create something like a new enemy.

For this post, I'll give a high level overview of how I designed the engine to be easily modifiable and expandable. In a later post (don't know how long from now) I'll go more in depth with certain aspects of the code and how it all works together. If you have any specific questions, feel free to ask in the comments. If the question is simple I may just answer it there, but if it is more long-winded I'll probably include it in the sequel to this blog post.

Since this wasn't my first attempt at designing a component based engine, I already knew one issue that I wanted to avoid, the overuse of components. Components are super helpful and great for abstracting out a specific mechanic or piece of code; but, they are only as useful as you make them. Just like anything else in development, they are a tool which can help or hinder you depending on how you use them. There's no point creating a design where each object is required to have 10 components, and while that is a gross oversimplification, overengineering can lead to some serious headaches down the road. Considering I'm only creating a 2D engine, I don't need an excessive amount of components per object.

So let's break down a basic enemy object into potential components, I'll use the example of a Goomba since it's easy to understand and most 2D platformers have their own example of an enemy with a similar movement pattern. The most basic requirements for a Goomba object can be broken down into a few components (X/Y position, Horizontal/Vertical speed + Gravity, Collisions and Sprite updates):

![]()

While some might argue that you could break it down into even more components, I like to believe in the KISS principle (aka, Keep It Simple Stupid). It's better to nail the fundamentals first before adding all the fancy trim so let's do just that. Out of the possible components I outlined above, we can start to predict what will be the basic structure of an object in our engine. Obviously the most important part of all the components is the position of the object, as speed/collisions/rendering are all dependant on the coordinates in a 2D space.

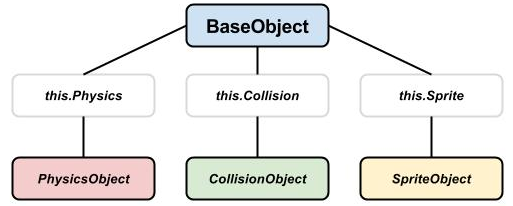

I decided to call the component which handles this most basic functionality the BaseObject, as all the other components are supplementary to it. I would normally call this the GameObject, but Unity already uses that name heavily and I don't want to fight against Unity THAT much. Let's give names to the remaining components as well to make this a bit easier to follow. The component which handles the horizontal/vertical speed and gravity will be called the PhysicsObject, the component which handles the collision event handling will be called the CollisionObject and the component which handles the changes in animation and/or sprite will be called the SpriteObject.

Now looking at these other non-BaseObject components, none of them are really required for a typical object. Not every object will need a PhysicsObject (stationary objects), not every object will need a CollisionObject (non-interactive objects) and not every object will need a SpriteObject (static sprites with no animations). BaseObject on the other hand is required, so let's build these three components to be optional extensions to the BaseObject component.

By structuring our model like this, we use BaseObject as a single point of reference for all of the additional components on the object. While the Update function is called for each component by Unity, we can instead have the BaseObject handle the updating of the other components instead, forcing Update to be called only once for the whole GameObject. Necessary? No. Clean? Yes.

So since I'm just giving a quick overview in this post, I'm going to avoid posting code or going too in depth with the functionality of each component. Instead I'm going to focus on the design decisions made to allow quick changes to these components to streamline the development time.

Let's start with the simplest case, the SpriteObject. This component doesn't need much more then basic functions to change the current sprite or animation time. In all honesty, I haven't gone into too much depth with this component myself yet as I've had no need to. We're only using development art at this time, so I would be wasting valuable dev time by trying to expand it at this point. Once I figure out the type of assets that we'll be using, I'll start thinking on how to extend the design of this component.

The PhysicsObject isn't exactly complex either, but it is important to have it easily modifiable. While each object tends to have it's own unique SpriteObject, the PhysicsObject doesn't require many variations. By using public fields for the force of gravity, acceleration, friction, horizontal speed, vertical speed and maximum velocity, it's easy to adjust the physics of the object directly in the Inspector. All the component is required to do is move the BaseObject via those values.

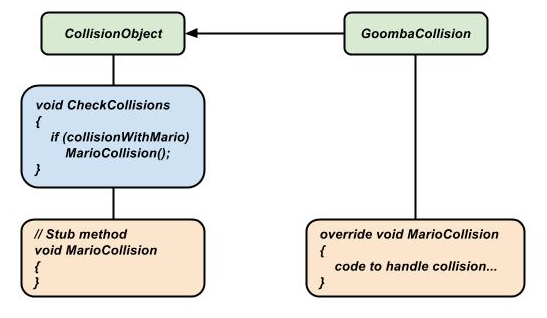

The CollisionObject component on the other hand is an important one to design to be modular. Each object will likely have it's own variation of the component, so we want to minimalize the overhead of setting it up. The best way to do this is to design the class to use mock handler functions. If we design the base CollisionObject class to detect collisions and call a function stub based on the type of object collided with, classes that inherit from the class can simply override the stub to handle the collision. This logic is illustrated in the diagram below:

This creates a desirable interface for handling collisions. Each object contains a script which inherits from the base CollisionObject class and defines the behaviour during different kinds of collisions. It doesn't get much more clean and simple then this, and it can take literally seconds to define the behaviour of a collision between two objects. Unlike the PhysicsObject the behaviour cannot be set in the Inspector, but handling collisions is fairly more complex than setting the speed of an object so this is to be expected.

While unique functionality of each object must still be defined by the BaseObject, we were successfully able to abstract out the optional logic for physics, collisions and sprites into their own components. Also by having these optional components accessible via the BaseObject, it is easy to cross-reference them in scripts. While some people may have their own opinions on how they like to structure their engines, I tend to like to take the most simple approach as long as it is still efficient. By creating my own engine it becomes a lot easier to streamline my development to my own personal preferences, which to me is extremely important. I like development but I like design better, so the more time I can spend on designing my game instead of dabbling in code, the better.