Intro

This devlog deals with time-based variation in Space Riot. As for Space Riot - the variation of the game itself not only lies in the three different game modes but also deeply in the amount of different enemies that maneuver around in different formations or paths.There exist numerous enemies that can be grouped into static ones like mines or non-static ones like enemy spaceships. But when and how should they be generated in a shooter like Space Riot? It's always hard for a developer to invent things that brings something fresh and more fun to the game and mechanisms to implement a more random and unpredictable feeling. And at the same time to reduce the amount of time that is needed to adjust these properties for the game designer.

With this article I will give you some insights on how it was achieved for Space Riot or how you can use this concept for similar games. The presented pseudo code should only be considered as concepts and don't always follow good programming practices of OOP. You probably will have your own architecture. So please keep this in mind when adopting those concepts. For this game I concentrate on generating enemies along the game. How can a more flexible architecture for time-based events achieved that is both easy to extend and to adjust for the developer and at the same time fun for the actual player? So lets begin.

Starting point

First, we have to define some game mechanics. As mentioned before, we have some static and non-static enemies. A goal might be: the longer the game is played the harder it should become. A simple approach would be that every x seconds an enemy is created on the screen://update method

if timeNow > lastTime + x

lastTime = timeNow //update lastTime

//create enemy

//update method

if timeNow > lastTime + x(i)

lastTime = timeNow //update lastTime

i = i + 1 % length

//create fighter and increase power

By this we only defined a periodic behaviour of creating enemies. If you want, for instance, a slowly increasing number of enemies appearing on the screen and then suddenly stop the process of creating enemies - you have to add another code block or add an if statement like this:

The if statement can lead to performance issues when this update method is called many times (but this shouldn't be an issue for this method - but think about it if you have a lot of code blocks like this). So you make two code blocks and check before:

And what if you want to create not just space fighters, but instead mine fields? Or both? You would have to replicate this code construct for every game entity you want to create or insert even more if statements - and that isn't a good code practice. The code basis will explode and error prone. Code maintenance will be very hard.

//update method

if timeNow > lastTime + x(i)

lastTime = timeNow //update lastTime

if(repeat == true) {

i = (i + 1) % x<sub>n</sub>

} else {

i = i + 1

}

if( i < x<sub>n</sub>)

//create fighter

//update method

if(repeat == true) {

if timeNow > lastTime + x(i)

lastTime = timeNow //update lastTime

i = (i + 1) % x<sub>n</sub>

//create fighter

} else {

if i < x<sub>n</sub> && timeNow > lastTime + x(i)

lastTime = timeNow //update lastTime

i = i + 1

//create fighter

}

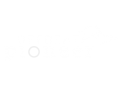

Time-based Events

Before, we can begin with the real work we need to define game events that we'll use later. A time-based event is a specific topic that is triggered by time. We are free to define those events. In the course of this article I'll define the following events:- MAKE_ENEMIES_STRONGER

- CREATE_FIGHTER

- CREATE_MINE

Of course, those events can also be used for other actions like collecting items or shooting enemy spaceships. Now we want to define when an event should be triggered.

Event Timeline Functions

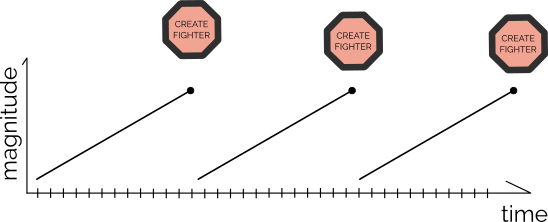

A better approach is to define a function that will tell us, at which point in time the enemies should be created. I call those functions Event Timeline Functions. With that we'll have all the freedom later. The first idea I mentioned can be formulated via a periodic function. Let's say we want to create enemies in constant time intervals. For that we can use a sawtooth wave:function sawtooth(t, x)

return (float) (((t + x - 1) % (x * 1.0)) / x)

With that we can do even more. Now we know when a peak is reached. This peak can be understand as an event and we know when it is happing in our timeline of the game. We can do anything at this point in time. We are not bound to just create space fighters for instance. The code would now look like this:

result = sawtooth(t, x)

if (result > 0.9) {

return CREATE_FIGHTER

} else {

return NONE

}

result = sawtooth(t, x)

if (result > 0.9 && !fired) {

fired = true;

return CREATE_FIGHTER

} else if (result < 0.9) {

fired = false

}

return NONE

The Game Event Handler

Okay, now we have that, but what can we do with it? We have events and an event timeline function. The next step is to implement a game event handler which takes care of all the event timelines and notifies us when an event happened. Not so much detail on the implementation just the idea. I implemented a thread and a message queue that operates in the background. This is a strong improvement. With that in mind, we can implement the publish-subscribe-pattern.//inside the gameEventHandler class (a background thread with a message queue)

for every event timeline function: eventTimeLineFnc

event = eventTimeLineFnc.activation(currentTime)

notifyEvent(event)

gameEventHandler.addSubscriber(enemySpawner, CREATE_FIGHTER)

gameEventHandler.addSubscriber(enemySpawner, CREATE_MINE)

//insde the enemySpawner class

event_callback(event) {

//do something with the event

}

Even if the game has to do heavy-load operations the background thread will operate independently and fire those events just in time. The game loop can then add game entities to the scene and they will get updated and rendered in the next cycle.

This architecture lets us easily define new behaviour without changing the code basis! Isn't that neat?

Summary

So what did I do? Basically, I implemented an asynchronous message queue that operates in the background and doesn't block our game logic and regularly checks for time-based events. If an event occurs, then it will notify its subscribers. According to the solid principle of OOP the appropriate object will create the enemy and not the update method itself or the event handler. Everything is well encapsulated.For a game designer it means: He/she only defines the function and the parameters - this change will instantly be available in the game.

if you have any questions please do not hesitate to comment.

if you have any questions please do not hesitate to comment.