Postmortem: The BM Hazard Course

Introduction

The Hazard Course add-on for the Black Mesa mod was in development for over three years before its release. Why is it that, even with several talented developers on the team, it has taken so long to develop what should be a relatively straightforward 20-minute level that involves neither real combat nor extensive set pieces?

In this article, we'll discuss several observations of our development process and identify various reasons for our relative inefficiency. Hopefully after reading this, people will better understand why the hell this project took so long. On behalf of all of PSR, I apologize for the ridiculous development time, and hope you thought the wait was worth it regardless. And to any aspiring modders out there: avoid these pitfalls! We took the hit the hard way, so that you guys won't have to!

A TL;DR summary section is waaaay down below, if you're not into this whole "reading" thing.

So... What Happened?

In these sections, we'll discuss observations of our team’s somewhat effective, but mind-numbingly slow level design procedures for the Hazard Course project, and attempt to gain a better understanding of the shortcomings of this approach. We'll discuss exactly why a lot of the things we did led to such a poor use of our time that developers were able to apply to college, finish several years of college, relocate living arrangements, and meet and lose significant others, plus many other things during the course of development… all before the mod even left Alpha.

The Initial “Land Rush” – Every Man for Himself!

When the Hazard Course was first (re-) proposed after the initial release of Black Mesa, there was enthusiastic support from the community. The initial work on the Hazard Course was done by Box, who created several prototype maps of the initial hologram room for display on the Black Mesa forums. This prompted several other users; Crypt, JeffMOD, and DKY; to jump on board as volunteers for the project. What followed was essentially an every-man-for-himself land-grab by each of the four initial level designers: each new volunteer rushed out on horseback and wagon into the great wilderness that was the Hazard Course, and when the young, naïve homesteader found a section that had not already been claimed, he slammed a stake into the ground, waved a flag, and proudly proclaimed that area of the mod “his”. He then engraved his declaration of ownership of that area into a nearby rock, and began to develop that area independently of everyone else on the team.

While these events were met with great enthusiasm and lofty visions, in hindsight it was a poor approach to an initial design phase for any project, great or small. This “land rush” created a situation that essentially boiled down to four separate developers working on four independent projects that ignored a central goal, other than a vague idea of “remake the Hazard Course”. As a result, no early coherent vision was formed, and each developer seemed to have his own ideas as to where to take his own particular section of the mod. This was only somewhat resolved much later on, when consistent communications were established in the form of Skype chats and semi-regular meetings. Unfortunately by that time, significant progress had already been made in the prototyping stages of each developer’s work. This meant that it was nearly impossible to establish a single clear idea of how the end product should turn out, without inevitably discarding at least one person’s hard efforts.

No Master Planning and Standards

The aforementioned lack of a coherent vision led to a number of issues during development. The first immediate issues became obvious once the team attempted to merge each of the independent sections into a set of maps playable from start to finish. Due to a lack of a master layout plan for the project, it turned out that the geometry of each independent section tended to be incompatible with the geometry of others. Essentially we were reduced to the adult version of trying to put triangle blocks into square holes, just like little Bobby the Two Year Old loves to do.

At best, this was a problem that forced a large amount of formerly clean geometry to suddenly become off-grid. At worst, it required major modifications to the layout of the areas, including full rotations of entire sections. Many times, the team resorted to using complicated “connector” geometry, thinly disguised as hallways, in a heroic attempt to “glue” the sections together. We forced the triangle blocks into the square holes by carving out ugly triangle-square adapter pieces, mashing the shapes together, and hoping that they would hold up. Then we stood back, patted ourselves on the back, and pretended that the end result was pretty. Upon seeing this monstrosity, Bobby the Two Year Old began crying for his mamma. Yuck.

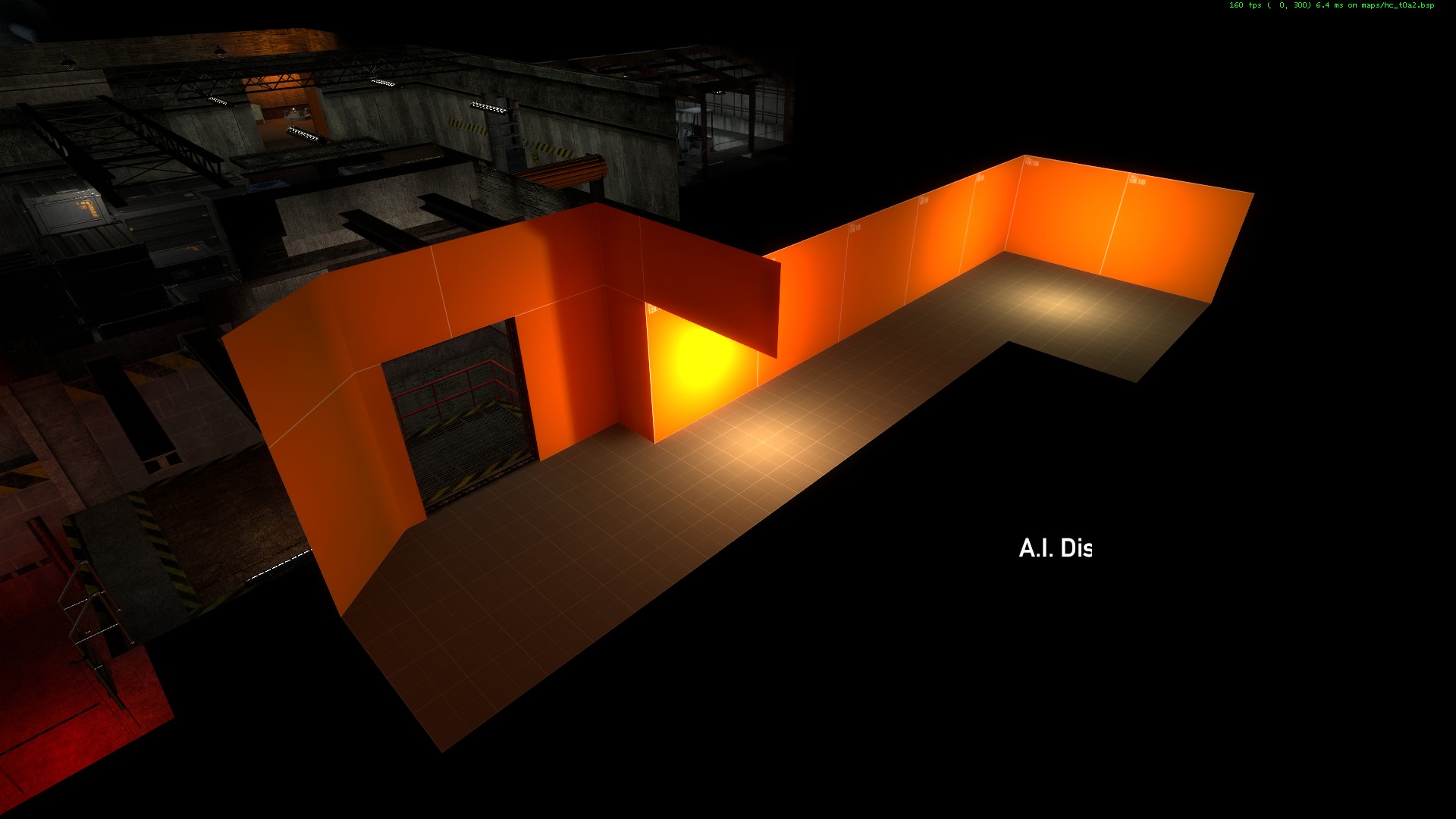

Several examples of "glue geometry" that we had to create specifically to connect incompatible sections.

(Click to embiggen.)

Worse still, some team members did not follow the same sizing conventions as others. This caused confusion when different sections of the mod were handed off to others for additional editing. For a long time, this lack of internal standards prevented the team from joining together and cooperating to improve the mod as a whole (see below for more on inconsistent collaboration). Had the entire team just stuck to a single set of standards, a lot of wasted time spent refactoring (and in some cases, redoing) the geometry could have been saved. And perhaps poor little Bobby’s tear ducts would still be intact.

See the next section for more on redoing large portions of work.

Excessive Rebuilding from Scratch

Especially because of a lack of standards, lack of a master plan, and lack of an overall vision in general, the team made the decision to scrap entire sections in order to redo them from scratch on multiple occasions. Sometimes it was due to messy geometry. Other times, it was because a developer felt like it could be done “cooler” (see the next section for more on that idea). Either way, it always resulted in wasted development time and a wildly unpredictable final product.

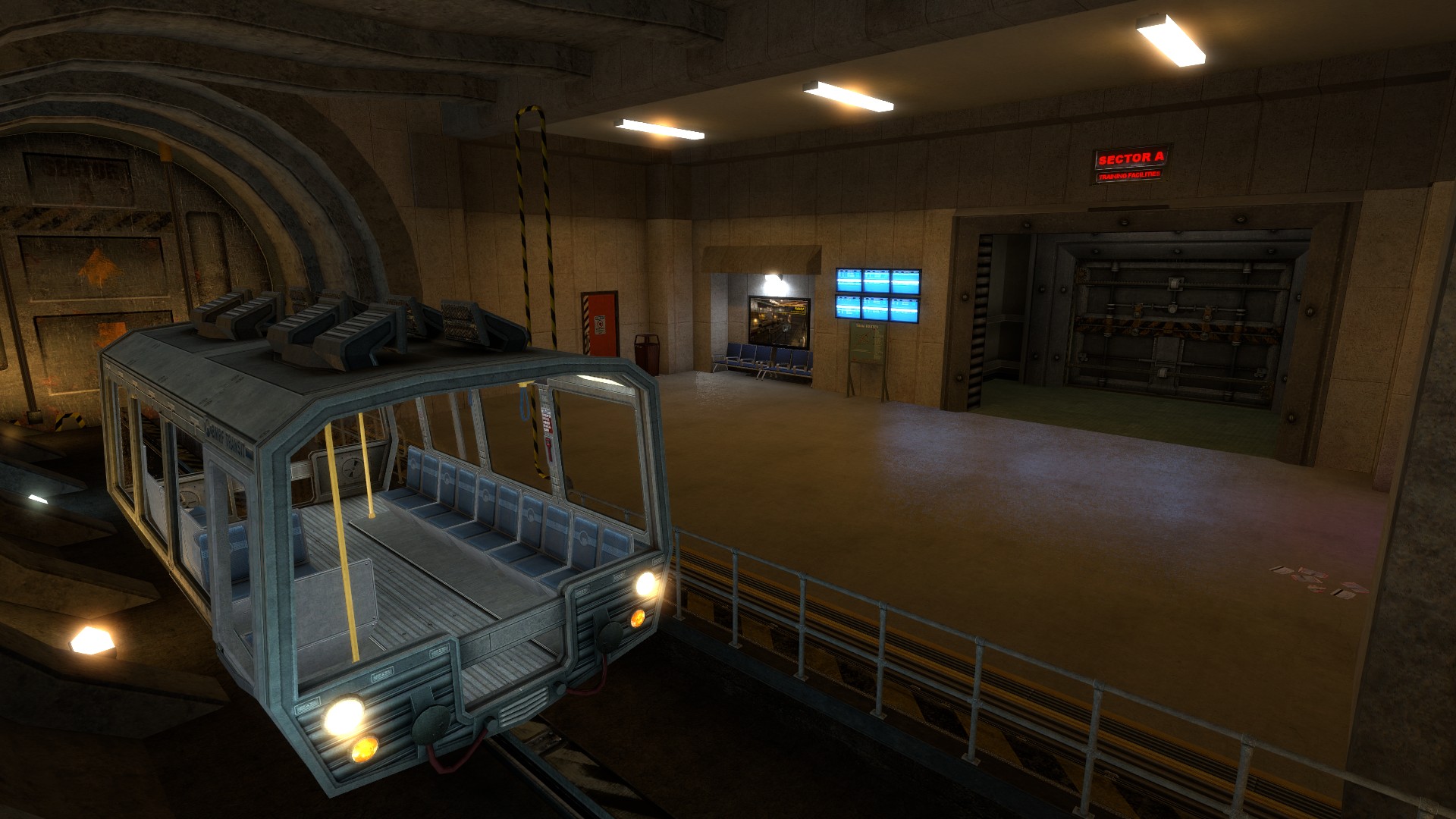

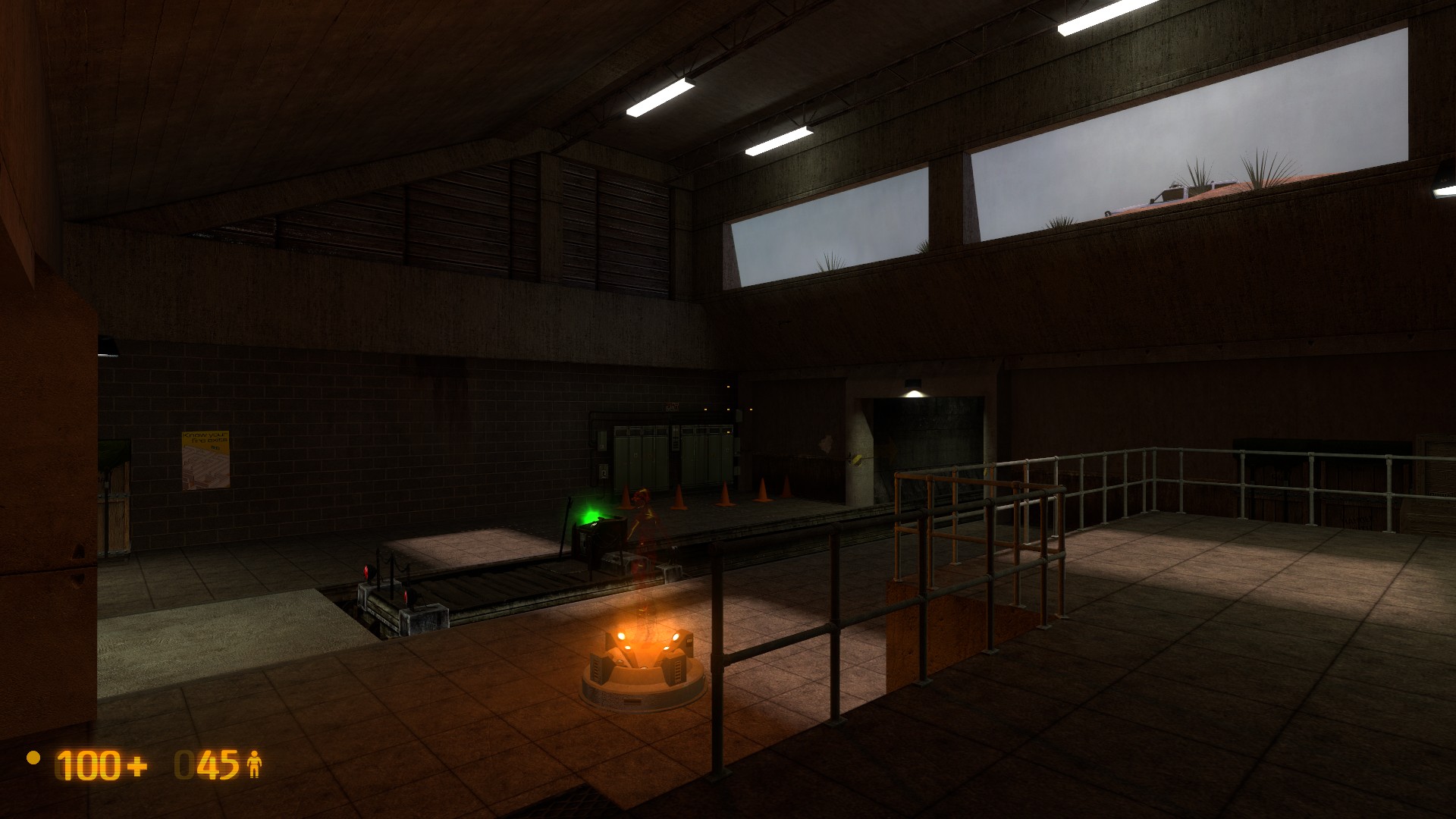

Evolution of the ending area.

We redid this area from scratch several times until we settled on the aesthetic in the bottom row.

(Click to make huge.)

Perhaps it would have been okay if these sections were just base orange-mapped prototype geometry in a concept stage, but more often than not, these were sections that had already gone through multiple detail passes and a lot of effort. This ended up invalidating all of the previous work done on those areas, which amounted to lots of time wasted re-doing what had already been done before.

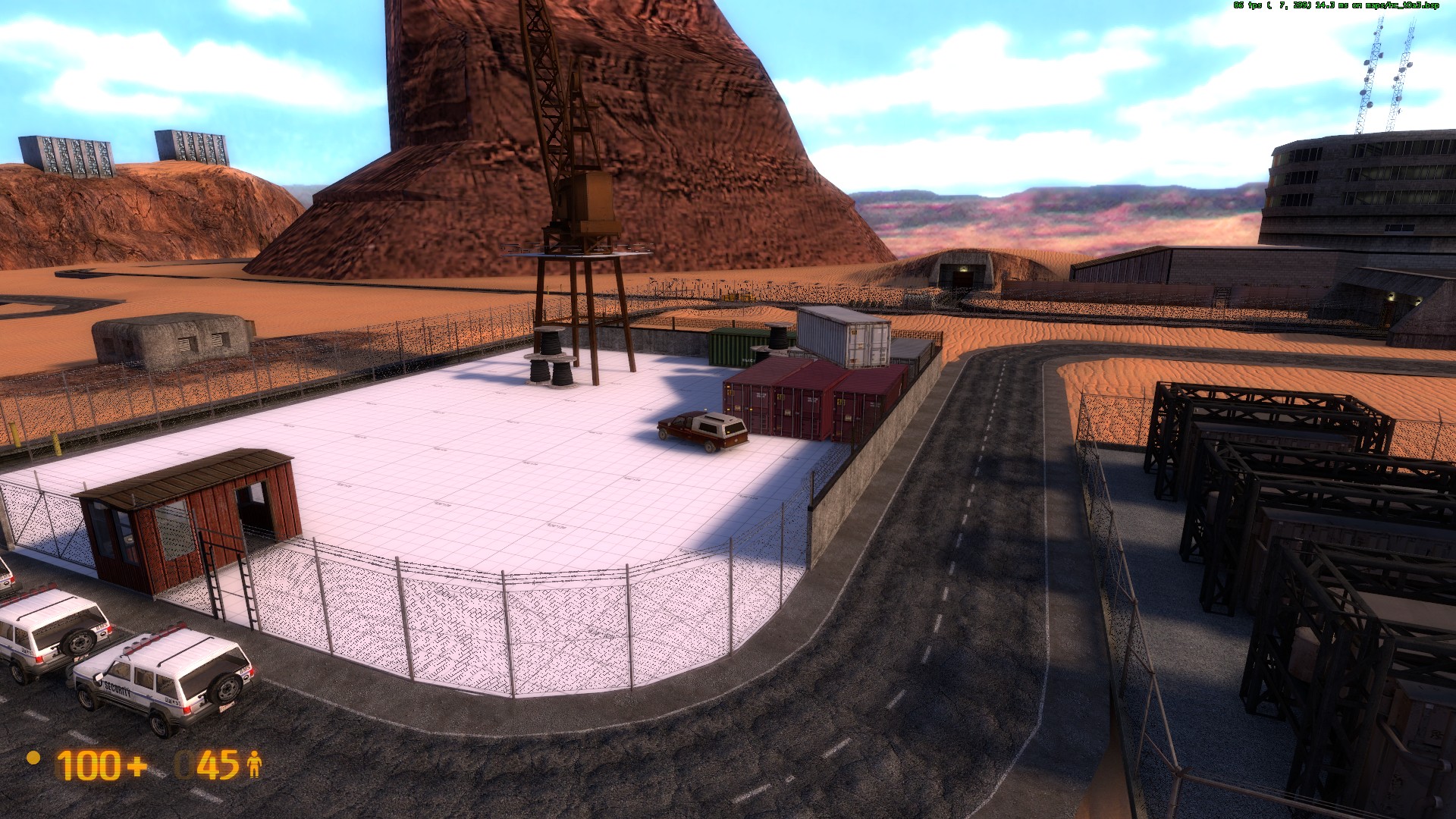

Evolution of the intro area.

We restarted work on this area several times, throwing away tons of existing work and polish each time.

(Click to make gigantic.)

Rebuilding things from scratch is almost always a bad sign of terrible things to come. Perhaps it would have been acceptable if it were just a room or two at a time. But the fact that the team came to the conclusion that this had to be done on many occasions for very large sections of the mod should have raised a red flag as a clear warning that we were wasting a lot of time and that something was not right. History tells us repeatedly that projects that restart large portions of progress, no matter the reason, are almost always bound to be extremely late, under-featured, or doomed to fail. Not convinced? I have three words for you: Duke Nukem Forever.

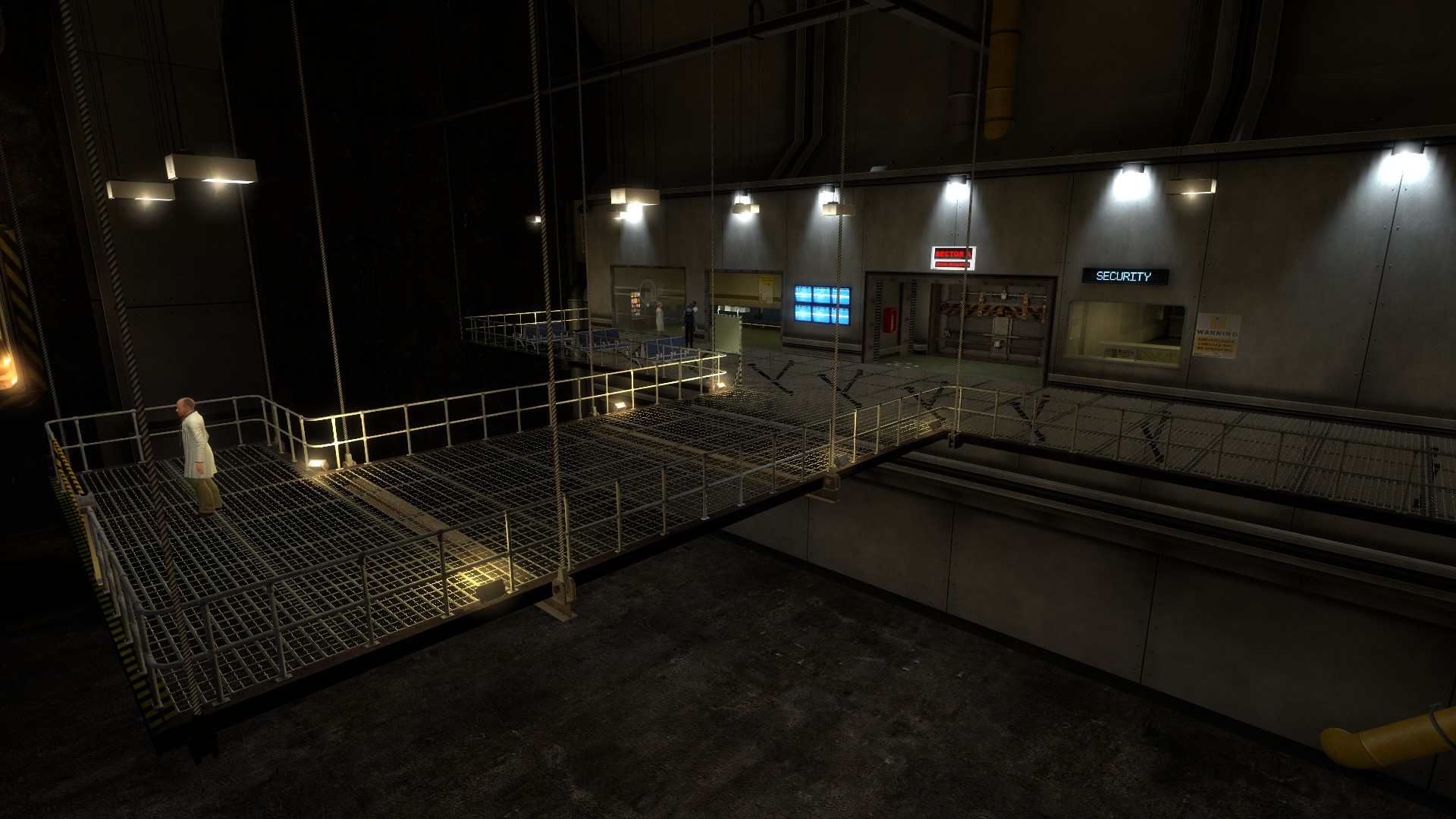

Evolution of the Tram Room.

The bottom row doesn't look much different from the top row, but trust me--

almost all the dimensions had to be redone and reworked.

(Click to enhugen.)

Feature Creep Syndrome

Some team members were too ambitious in their ideas of where the project should lead. Because the scope of the project was never laid out from the beginning, some developers would spontaneously get new ideas, and thinking they were good ideas, immediately implement them without firmly establishing that the ideas should be in the mod at all. This resulted in a project that was ever-growing in size, without a clear limit as to where it should stop. The attitude to new features was generally “if it sounds cool, why not do it?”, which, in hindsight, was a mistake.

Because the mechanics and features of the mod were never explicitly established from the beginning, the development team went through a very long period of time doing nothing but the following:

- Add new “cool” feature because why not?

- Test the feature

- Wow, this feature sucks

- Remove the feature/heavily revise the feature

- Repeat

Worse still, these new features commonly required extensive modification to the working copy of the mod, which caused the team to waste a lot of time simply tearing down entire sections because they did not work, then throwing up new ones hoping that they would be fun. Essentially, this was development by brute force by throwing a lot of absurd ideas into the build and hoping for the best.

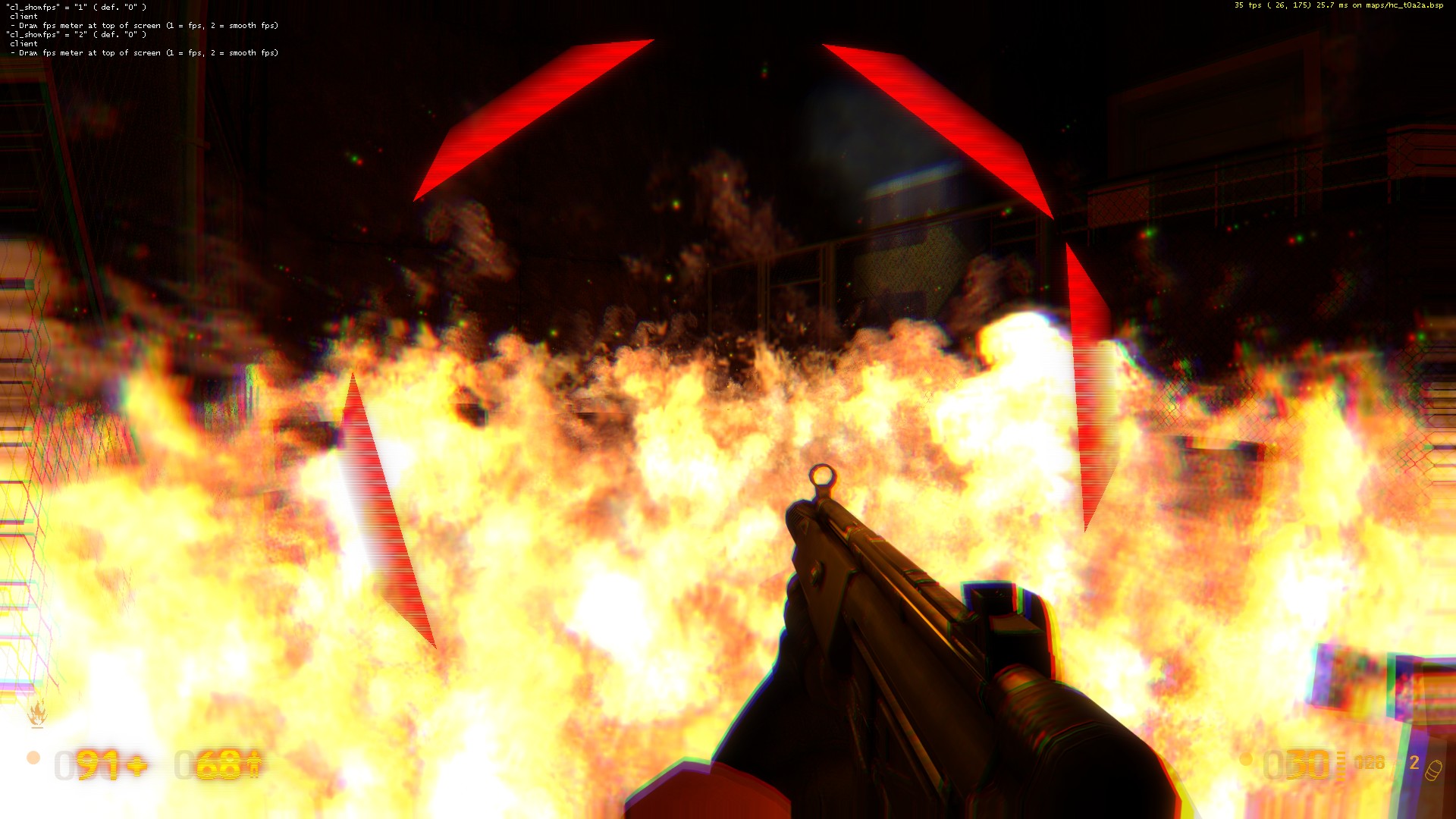

A small example of terrible cut features that had no place in the Hazard Course.

Clockwise from top-left: The Room Made of Fire, the Water Maze,

the Maze of Darkness, and the Robo-RangemasterTron Glock Delivery System.

(Click to hugeify.)

This did result in a few interesting new features being found and kept, but it also produced many, many more poor-quality ones that were thrown away. In the end, the development team wasted a lot of time just trying to spontaneously throw in cool features for the sake of throwing in cool features, when it should have been focusing on making the mod. The problem? We had no idea what “the mod” actually meant. (See previous sections on the lack of a coherent vision).

This phenomenon of a developer adding lots of unnecessary features that generally should not be in the scope of the project is known as feature creep, and the Hazard Course was a clear victim of it from early on.

Lack of an (Effective) Internal Schedule

Humans are procrastinators by nature. Without external pressure, we rarely bother to get things done if we do not want to do them. On the other hand, if we enjoy what we do, we rarely ever consider ourselves “finished” with our work if we are not given a very clear cutoff point.

In the case of the Hazard Course, development was wildly unpredictable due to the reasons mentioned in previous sections. As a result, an internal schedule could not be established for a very long time. This resulted in some developers doing nothing for long stretches of time due to a lack of motivation. On the other hand, this also resulted in excessive feature creep (see above) from other developers who were simply swimming with ideas. The few deadlines that were implemented (e.g. the May 4th, 2013 deadline fiasco) were too long-term to have any reasonable effect on team productivity, and in hindsight, were far too optimistic.

In early 2015, the development team decided firmly that the Hazard Course had been in development for far too long, and made the decision to release that year, no matter the cost. However, at the time, the Hazard Course was still in late Alpha stage, and not entirely feature-complete. The issue here was obvious: unless the team made immediate and extreme changes to the development cycle and reached Beta stage very soon, the 2015 goal could not possibly be met. With this in mind, the team decided to shift to a bi-weekly internal release schedule: internal builds, which used to have random, arbitrary deadlines, would instead be released every two weeks. This was a critical part of the bigger plan to reach Beta stage quickly. It was absolutely crucial that the Hazard Course hit Beta before the end of the summer, as several developers would be starting their university semesters after that point and become otherwise occupied.

The bi-weekly release schedule revolutionized the way the Hazard Course was developed. Every two weeks, the developers locked in a set of realistic goals to be met over the next two weeks, and each two-week release cycle itself had a larger overall goal attached to it (e.g. beautification pass on X areas complete, Y set of bugs fixed, all placeholder choreography implemented, etc). The larger goals themselves were broken down into smaller goals, called “tickets”, which could each be met in a matter of hours or days at most. These tickets were carefully partitioned out between each release cycle and assigned to developers, who marked them as “Complete” when finished. After each internal release, missed tickets would be re-distributed to future release cycles, and the build would be shipped off to playtesters, who would add new tickets to the system based on their opinions and feedback on the state of the mod, thus beginning the cycle again for the next two weeks.

The TODO list of tickets for the first Release Candidate build of the Hazard Course.

(Click to make absolutely gigantic.)

With this bi-weekly internal release schedule, the goal of reaching Beta by the end of the summer was accomplished with some time to spare, which was an extraordinary feat for a team that had been so disorganized mere months before. Only after these shorter, clearer impending deadlines were set did the team suddenly begin spurring into productivity. The lesson to be learned here is that deadlines are useless unless they are clear, immediate, and realistic. Long-term deadlines are almost completely ineffective.

Inconsistent Levels of Collaboration

Many mod teams approach level design by carving out the levels into reasonable “chunks”, and assigning each chunk to a different developer. Each developer is then responsible for everything in their designated area. Naturally, the Hazard Course easily fell into this pattern early on due to the land-grab that occurred from the beginning.

However, there are several shortcomings to this approach. The main problem with this is that it encourages each developer to be a “jack of all trades” level designer. Level design is a very, very broad field—it encompasses everything from player psychology and artistic design to AI scripting and runtime optimization. It is unrealistic to think that any one person is universally good at absolutely everything in the field of level design. So why put one person in charge of an entire physical section, which inevitably includes the entire range of skills necessary to create a great level?

As we very quickly found out, each member of the development team clearly had his own strengths and weaknesses. This is true for every development team, be it Valve, Bungie, the Crowbar Collective, or our own PSR. Arguably, the best, most well-rounded parts of the Hazard Course, such as some of the Hazard Rooms and the Guard Room, were those that were fleshed out through collaboration, rather than assignment of the whole area to one person for full development. Unfortunately, this idea was not applied uniformly to the entire project, and as a result, the overall quality of work per room is not always consistent between areas.

It was only towards the end of the project that we started to consistently combine our efforts to improve the entirety of the Hazard Course to higher levels of quality. Rather than “owning” specific parts of a level, each team member began to specialize more on what he did best. Facilitating this shift in development methodology was our ticketing system (as mentioned in the previous section)— each type of ticket was distributed to the team member best suited to that type of work.

Summary (The TL;DR Version)

The TL;DR version of the preceding sections is as follows:

- The initial land-grab caused the team to lack a unified vision for the project.

- The lack of master planning and standardization caused issues with cooperation.

- Lots of time was wasted rebuilding entire sections from scratch multiple times.

- The lack of a clear vision caused excessive “feature creep”, which wasted development time.

- Unpredictable development led to completely ineffective deadlines and scheduling.

- Lack of consistent collaboration on different areas caused inconsistency in quality.

So What Should I Do?

If you're an aspiring modder or developer yourself, you may be thinking: “Great, well now I know what to watch out for, but what should I do to avoid these pitfalls?”

Here's my advice, based on my experience with the Hazard Course:

- Establish a clear, unified vision among your team as soon as possible. Even if you're doing a solo project, make sure that you know exactly what you are doing. Some fuzzy idea doesn't cut it-- you need to be absolutely sure of what the player's experience will be like, and this vision should ideally be as detailed as possible. What can help is to write down your ideas in a common place where your whole team can see it (and possibly help edit it). This way, you can edit and revise your plans without having to tear down huge existing sections of your project. After all, it's much easier to change your ideas on paper than it is to change something that you already built!

- Establish a set of internal standards within your project, and make sure you strictly enforce those standards. Standardize as many things as you possibly can-- dimensions, colors, internal names, file names, file structure, and so on, and make sure everything you do is consistent. This way, you'll be able to collaborate with the rest of your team very easily. When you pass sections of your projects off to other members, none of them will have to deal with highly unfamiliar territory, and when it comes time to snap the entire project together, everything will be able to come together smoothly, with minimal work required. Even if you're doing a solo project, having a set of internal standards will ensure that you never have to guess or make something up (like a file name or a door size or a texture color) on the spot.

- Avoid tearing down and redoing an entire section unless you have a damn good reason to do it. The fact of the matter is, unless the area is so far gone that it's simply not salvageable, redoing huge sections of your project tends to be a bad idea. Redoing entire sections means a lot more time spent throwing away a lot of your existing hard work. Try and see if you can salvage what is already there, before giving up and starting over. If you ever find yourself redoing something from scratch, make sure you have a justifiable good reason to do it, and create a clear plan to make sure that the end result is actually worth the time you spent.

- I should mention that this does not mean that you should not tweak your existing work. By all means, if you think an idea could be better, you should iterate and improve on it. But try not to throw away the entirety of what you already did, unless you have no choice!

- Resist the urge to add unnecessary features, at all costs. Just because it sounds awesome, doesn't mean you should just add it in on a whim. If something is not part of your original unified vision (see above), you should think very hard about whether a new feature is actually worth the time. Make sure you discuss with your team and draw up a good plan before adding a new feature that just sounds “cool”, and make sure the idea actually fits in with your original vision for the project. Otherwise, you risk wasting lots of time throwing in and removing features that should never have been in the project in the first place! Another benefit of this is that sticking just with your established ideas gives you a very clear “finish line” for your project. Without a clear finish line, your project is just never going to be complete, and you'll just be facing an ever-growing pile of work that you'll never get done!

- Always keep a very clear set of current tasks among your team, divided into short, realistic deadlines. A ticketing system like Trac, or any similar project management or bug tracking system can be extremely valuable for any project. And if you don't feel like taking the time to set up an entire ticket system, at the very least have a TODO list posted in a public space for your entire team to see. Make sure your deadlines are clear, realistic, and immediate. Don't set a hard deadline for more than two weeks in advance-- you're not going to make it unless you get extremely lucky, you are extremely generous, or you are a goddamn psychic. A rule of thumb that I tend to use: assume that your project will take at least three times longer than you think, and plan accordingly.

- Divide up your tickets (or your TODO list items) into small, specific tasks. Don't write down a general, overarching task like “implement the foobar level”. Instead, break it down into smaller, specific tasks-- for instance, “add the foo room and the bar puzzle to the foobar level”, or even “implement entity logic for the spam ambush area in the foobar level”. A rule of thumb here is to make sure your tasks are measurable in hours, rather than days. The reason for this is that it forces you to create a plan of attack for everything, and lets you better estimate how long it will take to do it. After all, it's easier to guess how long it will take you to do a smaller task than a larger one!

- Use a version control system. Seriously, just do it. Version Control Systems are an absolute godsend to anyone working on any project, big or small. If you have no idea what a VCS is, it's essentially a piece of software you can use to record the history of any and all files in your project, which allows you to retrieve any older version of any file in your project. A VCS will also usually allow you to create different “branches” of your project, so you can isolate different versions of your project using different combinations of different versions of your files. For the Hazard Course, we used Subversion, coupled with the TortoiseSVN GUI to manage and develop the mod. Other notable VCS software that I might recommend (depending on the kind of project you're working on) include Git and Mercurial.

- Always be willing to share work among everyone in your team, and make sure everyone gets to focus on what they do best. Divide up tasks according to who is best capable of taking on each task. If someone feels most comfortable doing a particular type of thing, by all means let them do it. Collaborate as much as you can on the common areas in your project, and try not to “own” any large common sections of the project. If everyone specializes on what they do best, you'll ultimately get a much better project than if a single person does absolutely everything in one level, for instance.

Conclusion

This was just a small taste of the story of the development of the Hazard Course project. We screwed up big time for sure, and from that, we all paid the price of an extremely long development cycle. But if anything, we learned a helluva lot from this project-- how to work as a team, what things we should do, what things we should not do-- and we will definitely be taking these lessons to heart as we move on to bigger, badder projects.

In the coming weeks, the PSR team hopes to release a number of the original Alpha and Beta development versions of the mod, so that you guys can see first-hand how the Hazard Course evolved over time. Thanks to the magic of Version Control Systems (as I mentioned in the last section), we have preserved snapshots of the Hazard Course from years ago, so we'll be able to easily package those and release them to you guys to check out.

I'm also thinking of doing a commentary livestream of all the old versions of the Hazard Course, if there's enough interest for it. If you'd like to see this happen, leave a comment below (or on our forum thread), and I'll see if I can get a time in for that!

I hope this article helps other aspiring modders out there. If you have any questions at all-- about the Hazard Course, its development cycle, how we did what we did, and so on-- don't hesitate to contact me or anyone on the team. After all, our open-dev policy is still in effect! We really have no reason to withhold anything from you guys.

Thank you for all your support on this absurdly long journey. Your continued enthusiasm is really what kept this project alive over the years. We absolutely would not have finished if not for the knowledge that a lot of fans would have been disappointed if we just gave up.

Thank you again, and have a very safe, and productive day!

Thanks for this "deep" insight into your development phase!

I do understand why some people gave up hope on BM:HC [i never did, because (in such things^^) i'm a patient person], but this post clarifies the horrible delay. It is understandable that an new formed development team can't work together as flawlessly as they want.

I just want to say thanks for all of your effort to make this mod happening and cannot wait for (if there will be any) future developments.

Greetings

€: Oh, and about the "commentary stream" for early versions, i would be really happy to hear them :D

Great post-mortem! It's articles like these that can really help aspiring mod teams or indie developers in the long run, because I know for a fact, I've seen SO MANY mods that looked great, but never came to be because of many different reasons. Whether it be lack of interest, long development hell cycles, etc.

That being said, I'd be 100% interested in seeing you guys doing a commentary stream on the history of Hazard Course and how it has evolved over time. Keep up the great work! :D

I love reading these, you can get these sense that those working on mods and talking about the development learned quite a lot from the experience, even if the project crashed and burned.

I for one look forward to dev commentary on older versions, it would be quite fascinating to catch a glimpse of previous iterations with a devs eye :)

Nice postmortem, but you missed one crucial part: what did the team do well? You went into great depth about what issues arose and how they were handled, but what went right and what was the team good at? Can't be all negative.

Great point. Most of our successes came after we implemented the bi-weekly release cycle that I mentioned in the "Lack of an (Effective) Internal Schedule" section. As I mentioned in the article, after implementing the bi-weekly release cycle in early 2015, the development of the Course was basically revolutionized, and we were able to make Beta stage in record time. With that system in place (and with the pressure of making sure we could actually release before the end of the year), we started to be able to make absurd amounts of progress in ludicrously short amounts of time, which is the main reason why we were actually able to make the 2015 release in the first place.

Aside from that, most of our successes really just came about from AVOIDING all of these pitfalls. I actually wrote the majority of this article a couple of years back as an internal document, and edited it a bit for public release today. After I wrote it up and shared it with the team, we spent most of our time trying to fix whatever things we could, implemented the ticketing system, implemented bi-weekly internal releases, having the self-discipline to avoid unnecessary feature creep, and so on.

This is awesome I love reading this stuff just to get an idea on whats going on and stuff like this happens in any field films, TV and especially games. But you all pulled through and made it to the finish line.

I will finish reading this when i get home.

This article should prove to be very useful for any future/aspiring modders, for sure. Unfortunately it also convinced me (more like, confirmed my existing fears) that my (solo) project will never get finished since I cannot handle any sort of master planning, don't use VCS and, what else, yeah, keep redoing stuff. Please don't be like me, people.

It's never too late to start doing those things! :)

Not sure if it would've applied here... Because of the lack of direction, and the habit of coming up with everything on the fly, up until the point where you don't know what to do further, my project fell into a six year development hell and I was forced, upon reading the article and confirming what I already knew, to decide not to waste any more time on it. If I'm lucky, in a few monts, maybe by the summer, or maybe later, when I'm done with other projects, I'll be able to restart the mod with episode-based approach, but not until I have a full plan for it worked out, not until I know, as you said in the article, what the player experience should be like. Without that, it would be just as pointless as the previous six years of development.

I used to think that since I would always work on the fly that I couldn't pre-plan or that it would be a waste of time. In reality, that's an excuse you tell yourself because you don't want to plan. Trust me, planning is so much better. Not having direction doesn't keep you from planning, it's *the reason* to start. You spend less time on spur of the moment work that gets scrapped, establishes clearer goals and cutoff points, and gives a more cohesive vision of your project, both for you, and if you have one, your team.

I can tell you with absolute certainty that if we hadn't learned and began actually planning and organizing, HC would without a doubt still be stuck in the same Development Hell that it was for the first two years of development. It would not be out, it wouldn't even be kind of finished, and we'd have probably felt it was pointless and given up.

I used to "plan" in a sense "alright, I'm gotta be done with this chapter by %insert date% and will make a demo release at %insert date%". Obviously that got me nowhere. I tried to then plan by writing design documents but failed on that. How do you right one, for example? Do you actually draw a schematic layout of every map? It's hard for me to imagine not to do that on the fly, to be honest. And even then, what if I decide to edit something, a rather large part of the level? A new departure that needs additional amount of tweaking, and it all falls to pieces sooner or later. Spent more than 8 years with Source, never learned to fully make a map properly, so it seems.

It's all up to you. Like we say in the article, long-term, non-specific deadlines are pretty much useless.

For levels, drawing out layouts is great. I've recommended to people before to get a whiteboard, they're a godsend. Even if you're not great with scale or anything, it helps a lot to draw out your layout, sometimes even detailed room prespectives if you're up to it.

And yeah, of course things will need revision, and you don't need to stick to your original plans 100% if you find another direction is better. The point is to make sure you have direction at all.

Writing up design docs in my experience is mostly only hard at the start. Once you've picked a spot and start fleshing out it'll come more naturally.